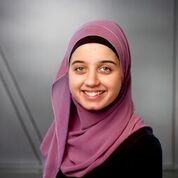

In my humble opinion, the world needs more people with the social conscience, kindness, intelligence, maturity, and quiet determination of Rida Hazim.

Fleeing Lebanon just before her birth, Rida’s parents came to Australia as migrants with her older sister:

“There was a civil war between Syria and Lebanon. My parents decided it was too politically unstable to raise their children there, the infrastructure is not there, there’s no twenty-four hour electricity, and there’s no running hot water. In fact it’s quite third-world; there’s a lot of disparity between the rich and poor and most people live below the poverty line.”

Rida has returned to Lebanon and describes it a “beautiful country” which is “very westernised, and very accepting of art, science and culture”. Aside from her uncle, all of Rida’s relatives still reside in Lebanon, and this makes the decision of Rida’s parents to build a life in Australia all the more remarkable.

Rida says the attitude, sacrifices and work ethic of her parents translated to them being strong role models growing up:

“My parents are two of the most amazing people in the whole world, they sacrificed so much and built something from nothing. Imagine starting anew in a country where you don’t know the language, you don’t know anyone, you have no money to your name, but you’re doing it for your future. It’s very admirable.”

Despite her parents being university educated, their qualifications did not have an equivalent within the Australian education system, and consequently, Rida says they“worked their butts off”:

“My dad had to work three jobs at sometimes 21/ 22 hours a day, so we didn’t see him a lot growing up. Now that I’m grown up, I can see that he was doing it to provide so that we could have food on the table.”

Raised in a household where education was valued above almost all else, – “education changes your life”- Rida studied accounting and finance as a double degree. In February 2015 Rida was accepted into the National Australia Bank (NAB) graduate program. On the program induction day, she was told about the NAB African Australian Inclusion Program:

“The program provides work experience for African migrants who have had corporate work experience in their home country. It’s a six month internship in an entry-level role at NAB where participants are paired with community mentors. I love being involved because my parents were in the exact same situation as a lot of our participants. I feel a real affinity with it.”

The program was introduced in 2009 with three participants, and at last round, fifty-three participants were accepted. Since its inception, three hundred people have been through the NAB African Australian Inclusion Program:

“We have so many success stories, it’s such a confidence boost and the amount of personal development is incredible.”

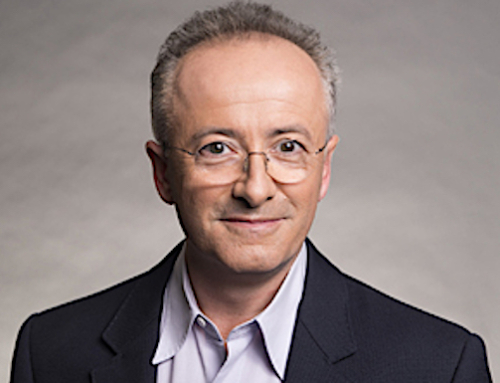

One such champion of the NAB African Australian Inclusion Program is Perth native Mike:

“Mike attended the Sydney branch of the program in February 2015. Like many of the participants, he was university educated overseas but then coming here he couldn’t find work, so he was working as a cleaner and in a factory. Mike’s wife witnessed him losing his confidence, retreating into his shell, and becoming a different person. Through this program, he wore his suit for the first time in years for a job interview. His wife looked at him in the suit and said, ‘Now you’re back!’. He got a permanent role at NAB. He stayed for a year but was finding it difficult to be away from his family. As part of the support network of the program, we provide participants with a coach and a mentor. They knew he was struggling with living a distance away from his family, so they found him a role in Perth, two positions above his current position. He had no idea everyone at NAB was orchestrating the move back home for him: “I never would have thought I would be sitting at a desk in the building I used to clean!”

Mike’s story is only one piece in the mosaic of life at NAB. The diversity of the workplace is a great source of pride for Rida:

“NAB is really good because you have different groups, so for example, a sector called NABility works a lot with people with disabilities and people who face accessibility barriers to assist with increasing inclusion. They are faced with questions such as, ‘How can we change our websites to make them more inclusive?’. There is also an LGBTIQA program called ‘Pride at NAB’. At the core of NAB’s company vision is the notion that we can make the world a better place, and empower people to make a difference….”

In a sense, this company heterogeneity protects Rida from the discrimination she has witnessed in other aspects of her life. The twenty-three year old Muslim woman volunteers at Preston Mosque teaching Arabic and religion to four- and-five- year-old children. All too often the mosque is confronted by protests from far right-wing Australian patriotic groups:

“They come on to school property or leave notes or souvenirs related to their cause, which is obviously very insulting.”

Rida’s primary concern is that such protests can gnaw away at the innocence of her students:

“Parents are sometimes too scared to send their kids to school because they don’t want them to be targeted. The children are exposed to the yelling , the shouting ,the pushing , the insults and the swearing, all at such a young age.”

As a proud Muslim, she suggests that the blatant negativity expressed towards her culture is due to an ingrained fear of the unknown:

“The most common misconception surrounds the teachings of Islam. People are (very loudly) misinterpreting it all over the world, and all over the news. They try to justify their own actions using the religion. It does get frustrating when we see the attacks happening overseas and here, however there is a strong misconception that Muslim leaders aren’t doing anything to stop these attacks. There has actually been a lot of condemnation , a lot of reports and articles written by religious and political leaders, it’s just that people are not listening. The people who are being ignorant or racist are doing it on purpose because they are choosing not to see that side of the world.”

Rida believes the path to understanding cultural diversity, and therefore bringing about peace, is ensuring open and educated conversations with people of all ages. With that, she explains several aspects of her Islamic culture:

“My head piece is called a hijab and it’s a commandment from God, it signifies your relationship with God and your faith in him. Some Muslim females choose to wear it, some not; it all comes down to interpretation of religious text. My whole family is Muslim and we speak Arabic at home. My older sisters and I only learnt English through going to school, but my younger siblings learnt it through us.”

Being a member of a misunderstood cultural group forces you to grow up faster, denying you the pleasure of childhood naivety:

“You always have to be aware of what’s happening in world news so we didn’t really ever have the privilege of growing up not knowing about international politics. You’re always on the defence.”

Rida’s spirit is exemplified when she is asked about her hobbies:

“I don’t see the community work I do as strenuous, it’s something I love to do, so my hobby is giving back.”

Yet in other ways Rida’s idea of a fun day out is typical of a twenty-three year old:

“I check in with friends, – I’ve got a really close group of girlfriends I’ve been friends with since high school – I get coffee and network.”

As is common in Middle Eastern cultures, family is central to Rida’s life:

“I like to go to the movies every few weeks with my siblings, and one of my goals for 2017 is to send my parents to do their pilgrimage.”

This pilgrimage, known as the Hajj, is an Islamic journey to the city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia., echoing a journey travelled by Muhammad in AD 632. The Quran commands that every able-bodied and financially-stable Muslim make this journey at least once in their lifetime. The annual pilgrimage takes places from the 8th to the 12th of the last month in the Islamic lunar-based calendar. The Hajj involves a series of rituals, two of which are circling the Kabba (the cube at the centre of Islam’s most sacred mosque) seven times in a counter-clockwise direction, and praying from noon to dusk at the Arafat Valley, where Muhammad presented his final sermon. At the end of this pilgrimage there is a big celebration which involves praying at the mosque or at home, and then gathering with loved ones for a feast.

Perhaps the most celebrated Islamic tradition is Ramadan, thirty days of fasting every year, observed to acknowledge the Holy Scripture being revealed to the prophet Muhammad. At the conclusion of the fasting period another feast is held.

Rida takes a lot of comfort from her faith, and endeavours to act according to a teaching in the Quran, which when paraphrased means:

“Do good and good will come to you, for is there any reward for good other than good?”

It follows,therefore, that when asked how she would like to be remembered, Rida humbly says:

“I’d like to be remembered as someone who was always there to help, give advice, and get things done.”

More content out of the spotlight – “I like to enable people to have their moment to shine“, Rida says she prefers not to entertain a long-term plan for her life:

“I take each day as it comes. It would limit me to have a really clear vision because I like to pick things up and run with them.”

Who can blame her? This love of spontaneity has brought about her involvement in some extraordinary projects:

“One of our past participants of the African Australian Inclusion Program comes from a small island off South Sudan. He had to flee his hometown to this little island with his family during the war and his house got burnt down. He has to row forty minutes to get to school on the mainland . The boats are really rickety, they constantly have to throw out water using buckets. He had an idea to build a boat and have it be government-funded instead of using boats from local fishermen.”

Rida is heavily involved in fundraising for the boat and conducting analytics in order to ascertain the best materials with which to build the vessel.

Rida has vast experience working in analytics, given her permanent full-time role at NAB as a Portfolio Services Analyst:

“The Australian Investment Committee allocate money for different projects, so NAB for example gets about one billion dollars every year for projects instigating company change and projects aimed at assisting the customer. NAB is really focused on how can we improve our relationships with our customers, so my role is to conduct the financial analytics behind different business cases. My team escalates our findings to another committee where they make decisions on what projects get accepted or not accepted.”

Rida says although she immensely enjoys her day job, it is extra important to do a “damn good job”, so that she can dedicate extra time to the African Australian Inclusion Program where her true passion lies:

“I’m really passionate about diversity and inclusion whether it be gender or race or religion or disability or ability , that’s what I’m passionate about.”

In an era where the world seems to be enduring so much devastation, whether it be violent acts borne of hatred and ignorance, or the aggressive acts of Mother Nature, Rida maintains her optimism by remembering a quote by Fred Rogers: “Look for the helpers”.

Rida believes:

“Having that lens on life is a lot more uplifting, it is easier to process hardship when you know that there’s still people trying to do good.”